Blockchain governance - Part 3

Part 3

Basic Architecture Types

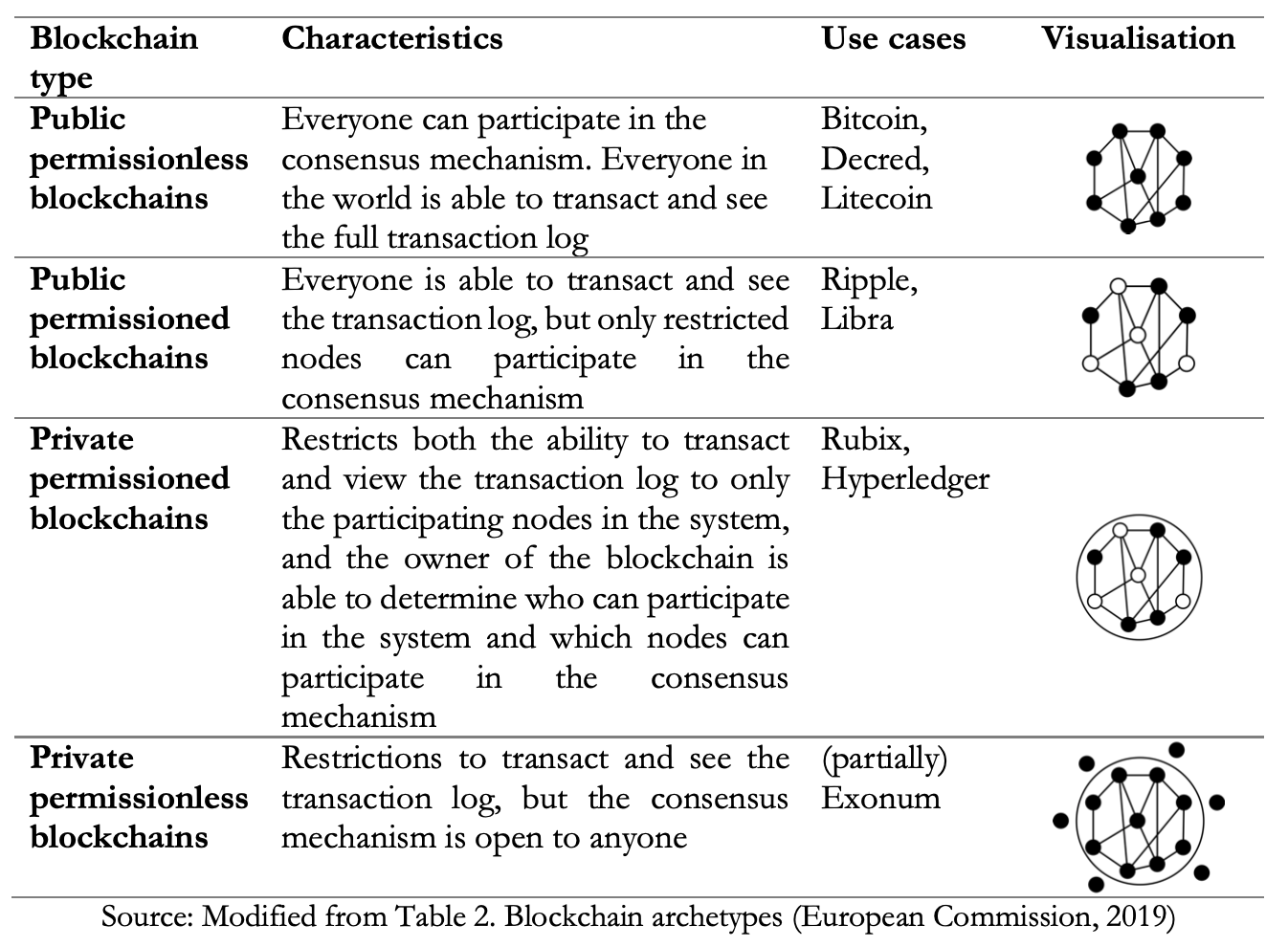

Blockchain architectures can be categorised regarding the openness of transaction validation (validate/commit) and the openness of participation (read/write) in the transactions (European Commission, 2019). The right governance architecture is paramount to deliver the freedom and power the users demand:

- Permissionless: anyone with the right hardware can validate or commit transactions.

- Permissioned: only a number of selected nodes can validate or commit transactions.

- Public: anyone can participate in transacting using the protocol.

- Private: only selected participants can participate in transacting using the protocol.

**Table 1 – Blockchain archetypes**

The black dots are the validating nodes, meaning that they are able to validate the transactions in the network and participate in the consensus mechanism. The white dots represent participants in the network in the sense that they are able to transact, but they are not able to participate in the validation or in the consensus mechanisms. The ring indicates that only the nodes within the ring can see the transaction history. The visualisations without a ring mean that everyone with a connection to the Internet is able to see the transaction history of the blockchain (European Commission, 2019).

Among the permissioned blockchains in production, the one that caught everyone’s attention is Facebook Libra. Libra claims to provide digital currency, but its whitepaper shows an intention to provide digital banking instead. The network is not open to any volunteer wishing to co-participate and help secure the blocks. To be an associate, the firm must buy voting rights, where USD 10 000 000 gives the rights of one vote (Facebook, 2019).

The Libra Reserve management will execute the Reserve Management Policy, which includes overseeing the “process of minting and burning Libra”. As fiat money enters the economy, the reserve grows, the association mints Libra accordingly, and the reserve is invested in low-risk and high-liquidity assets. Third-party liquidity providers will be allowed to exchange Libra for assets in the reserve (Facebook, 2019). It is very close to what Hayek envisioned in a time without the technology to remove the trusted third party, when he wrote that he would call institutions free to issue notes as simply ‘banks’, or ‘issue banks’ and “would announce the issue of non-interest bearing certificates or notes, and the readiness to open current cheque accounts, in terms of a unit” (Hayek, 1990, p. 46).

The Libra Network management will have the responsibility for the definition of the “process for managing the Libra protocol specification source control repository, including the process for reviewing and accepting changes to the protocol” and the rights to “explore permissionless blockchain technologies, and recommend to the board and council paths for transition to such technology” although such transition may never happen. The Libra council will publish recommendations suggesting the change of rules that will result in a ‘hard fork’, allowing the council to propose breaking changes to the Libra protocol (Facebook, 2019).

In a permissioned network, like Libra, the entity controlling the majority of nodes can freeze accounts, block payments and other messages. In permissionless networks, like Bitcoin and Decred, the majority of nodes decides the consensus rules and the acceptable transactions. As long as the honest nodes keep the longest chain, the network does not depend on a trusted third party, as shown in the next section.

Bitcoin governance and consensus rules

One of definitions given by Rhodes (2007) to network governance is “game-like interactions, rooted in trust and regulated by rules of the game negotiated and agreed by network participants”. Regarding public administration and public policy, he further explains that the “literature on governance explores how the informal authority of networks supplements and supplants the formal authority of government. It explores the limits to the state and seeks to develop a more diverse view of state authority and its exercise.” (Rhodes, 2007, p. 4). This section approaches governance from a private perspective, but the following sections will also approach the public governance.

In a peer-to-peer network blocks are broadcasted and may not reach all nodes. Nodes consider the longest chain as the valid one and will work to increase it. If a node receives two different blocks, they work on the first, keeping the other in case it becomes the longer chain. Not all nodes are miners, only those that work to extend the longer chain by validating the blocks. Other nodes just keep a copy of the distributed ledger (Nakamoto, 2008).

In a decentralised network, where nodes do not know each other, changes in consensus rules, like the block size, happen through block signalling. Miners use online messaging boards to agree on a binary signal to be carried inside blocks in a range, looking to build majority. In case of majority, the changes are implemented and kept in the longest chain, thus the time and electricity spent will be rewarded (Nakamoto, 2008).

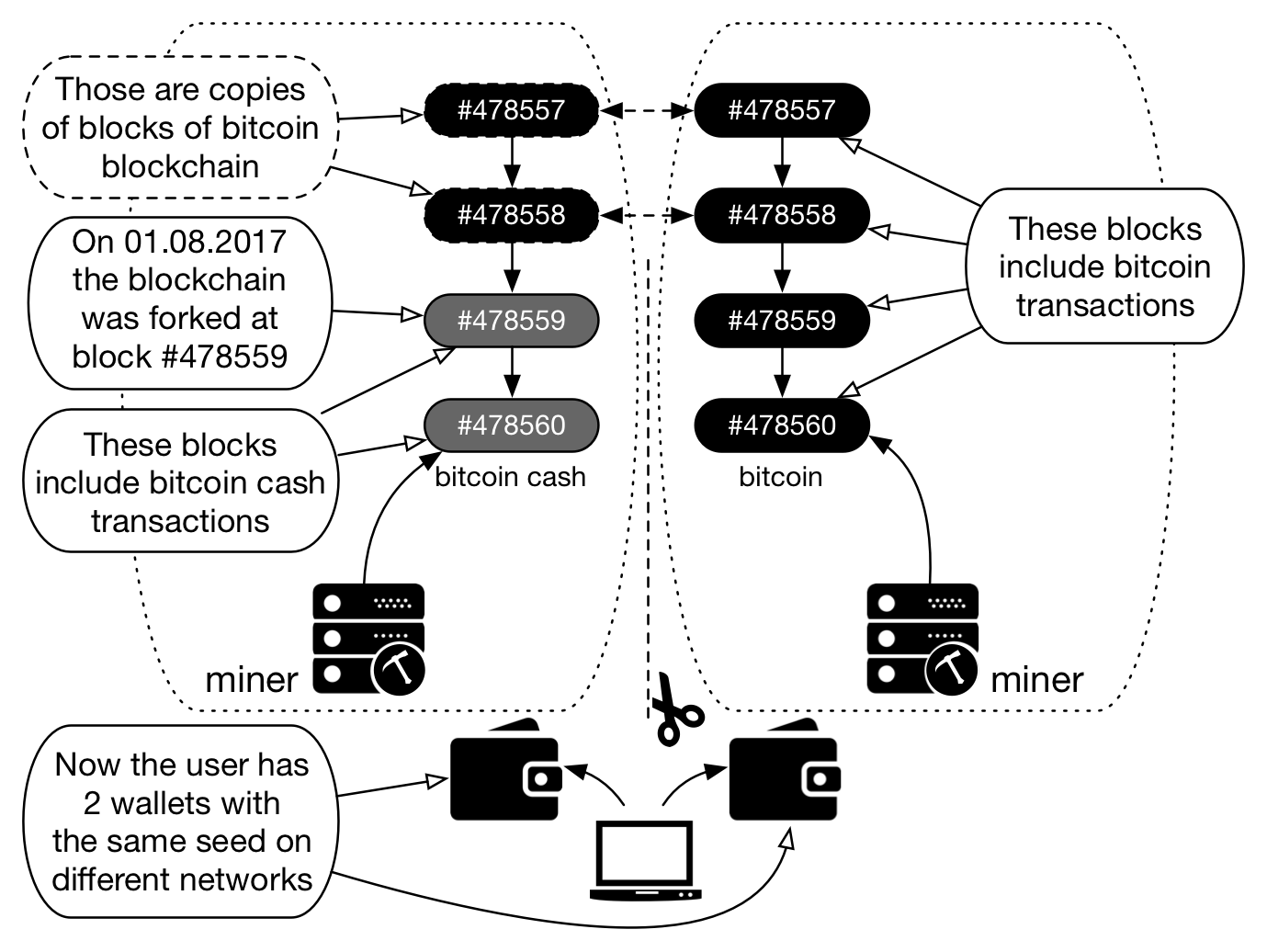

The minority must choose to accept the majority’s changes or ‘hard fork’. Because the nodes keep a copy of the blockchain, they have all the history. A blockchain hard forking keeps the history of blocks and transactions until that point, but deliberately start working on a chain that will not be accepted by the majority because of its rules and characteristics, thus creating another network that will have its own utility value and coins that will have different market value and name. Bitcoin governance is solely based on proof-of-work as the decision-making tool and Figure 2 depicts a blockchain fork on Bitcoin network.

Figure 2 – Bitcoin network right after the Bitcoin Cash 'fork'

Source: own elaboration

Blockchain governance may also be captured by the mining equipment producer, a player that has economic incentives to control how the blockchain rules should change, steering decisions towards its preferred direction. This is the case for Bitmain Technologies, a private Chinese company that dominates the ASIC-based cryptocurrency mining hardware industry, with approximately 75% of the global market share, and also the largest player in the mining pool services market. “Bitmain fully owns and operates two of the largest mining pools, AntPool and BTC.com, and is also the main investor in another large mining pool, ViaBTC. Many of the other large mining pools are also business partners of Bitmain. (…) By acquiring a large share of the pool services market, the equipment producer has a disproportionate influence on the governance of the blockchain.” (Ferreira, Li, & Nikolowa, 2019).

Privacy and fungibility

Considering the provisions in the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) for data minimisation, pseudonymisation and anonymisation, specifically article 5 (1), points (b) and (c), personal data shall be collected and processed with legitimate purposes and limited to what is necessary (European Parliament, 2016). At the same time, governments increase the processing of personal data to control political contributions, foreign donations, to fight terrorism, money laundering, and increase taxation and avoid money evasion. “Merchants must be wary of their customers, hassling them for more information than they would otherwise need” (Nakamoto, 2008, p. 1), because of regulations and to prevent frauds.

Blockchains allow the exchange of digital assets minimising or completely avoiding the processing of personal data by relying on public key cryptography to prevent frauds, which increasing privacy but reducing the control enforced on the individuals by the government. Privacy solutions involve running a local copy of the blockchain and also of the block explorer, a web application capable of graphically displaying blockchain data in human readable format, because web servers and applications can log IP addresses and allow the geolocation of users. Blockchain transactions can also be routed through the Tor network, also called ‘deep web’, an encrypted and log-free network of individuals, allowing for transactions, e-voting and political contributions in dictatorships and struggling countries. The mixing technologies coded in blockchains allow for the scrambling of transactions into smaller amounts, mixing several different inputs before they are outputted in a wallet, providing fungibility and significantly reducing the probability of identification.

Blockchain beyond the digital money

Although blockchains are usually related to digital money, the technology allows other applications like digital notary, transparent procurement and accountability and e-voting.

Identity and timestamping machine

In 2007, Estonia developed a blockchain technology that “makes it impossible to change the data already on the blockchain.” With timestamping, “history cannot be rewritten by anybody and the authenticity of the electronic data can be mathematically proven.” Timestamping works by creating a hash of an information an anchoring this hash into the blockchain. This way anyone can prove that an information or document already existed at some point in time, like a digital notary. Estonia claims that hackers, system administrators, and not even government itself could untraceably manipulate the data (Enterprise Estonia, 2019).

Government procurement and innovation programmes

Fraud and abuse of taxpayers’ money in government procurement and innovation programmes are common and it is not possible to determine how much taxpayers’ money is wasted every year. A 2018 OECD report shows that 42% of the employees of SOEs (State-Owned Enterprises) participating in a survey answered that corrupt or irregular practices took place in their company in the previous three years. Because SOEs account for approximately 22% of the world’s largest enterprises, this problem cannot be understated (OECD, 2018). It continues explaining that the greatest obstacles facing SOEs are related to human behaviour and relationships. The first three obstacles in order of appearance are: a lack of a culture of integrity in the political and public sector; a lack of awareness among employees of the need for, or priority placed on, integrity; and opportunistic behaviour of individuals (OECD, 2018).

Transparency minimises the problem of information asymmetry, but it can’t solve the agency problem or reduce conflicts of interests and power imbalances created by the human behaviour. For these problems, e-voting might be helpful.

E-voting and new models of governance

Power imbalances and information asymmetries between governments and citizens have historically led to profound social inequality and hierarchical power structures, often making it an arduous task to achieve non-dominating ideals. Corrupt governments and dictatorships can always use the system and rules against the citizens: “voting rules can intensify existing risks in the system that include the complexity of voting rules, the cost of voting, the limited hours of in-person voting, outdated voting machines, voter registration problems, challenges with mail-in voting, delays in counting ballots and the potential for administrative errors that invalidate or – perhaps even worse – indicate a vote for a candidate other than the one the voter intended”. Some of these problems can be mitigated with blockchain technology, because it maintains a timestamped immutable audit trail implementing checks and balances throughout the electoral process. It is possible verify the vote, which decision was taken and when, without linking a voting transaction to a particular voter (Johnson, 2019, p. 343).

Public and private governance depend on choices like direct versus representative democracy. Public governance depends on locally provided public goods (funded by a general tax paid by residents) and positive cross-boundary externalities. The preferences for public consumption and higher taxation depend on the capacity of the participant in free-riding other regions or participants. In the case of private governance, it depends on the private treasury, how it is funded and what it funds (Redoano & Scharf, 2004).

Blockchain-based governance can solve and replace centralised organisations and the problem of scale, where the State and representative democracy have been a solution so far, used to reach consensus and coordination between heterogeneous or distant groups of people, bridging the gap for mutual interactions. But governments are exposed to risks like lack of transparency, corruption, regulatory capture, misuse of power and authoritarianism, due to concentration of power, which leads to another problem: ‘Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?’ (Who will watch the watchmen?) (Atzori, 2015, p. 6).

As part of an anti-government phenomenon in Western democracies during the last decade, public governance has evolved to become more collaborative, decentralised and multi-stakeholder to “address the growing need to experiment an entrepreneurial model of leadership, finding innovative solutions to the mismanagement of State and bureaucracy across the traditional organizational and institutional boundaries” (Atzori, 2015, p. 13). Several countries are already using blockchain-based solutions to improve governance and voting trust:

Switzerland

The issuance of a blockchain-based government identity, certified by the City of Zug, started on 15 November 2017 and is called uPort. The app links a unique and unchangeable crypto address to the local user wallet. It aimed to expand its reach to other public services, like e-voting, bike renting, book borrowing, tax declarations or parking payments (European Commission, 2019). The e-voting trial started on 25 June 2018 and was a success, involving citizens that put their voices forward in a consultative vote via smartphone on an invented issue (Meyer, 2018).

Estonia

The Estonian blockchain records the ownership of securities as reported by the Central Securities Depository (CSD). The system issues voting right assets and voting token assets for each shareholder. Voting tokens (Proof-of-Stake mining) can cast their votes on meeting agenda items if the tokens own voting rights (Nasdaq, 2017).

Thailand

In a live e-voting process held from 1-9 November 2018, Thailand’s Democrat Party elect its leaders in a primary election and became the first political party to use blockchain technology to allow more than 120 000 party faithful to cast their votes in a transparent way (Nasdaq, 2018).

Brazil

VotoLegal app used Decred blockchain not record votes but to register campaign donations and keep candidates accountable, tracking the donation figures and who was the donor (AppCívico, 2018). Decred Project will be inquired in the next section.

References

AppCívico. (2018). Voto Legal Blockchain Explorer. Retrieved from Voto Legal: https://blockchain.votolegal.com.br/

Atzori, M. (2015, December 1). Blockchain Technology and Decentralized Governance: Is the State Still Necessary? Retrieved from SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2709713

Enterprise Estonia. (2019). KSI blockchain. Retrieved from https://e-estonia.com/solutions/security-and-safety/ksi-blockchain/

European Commission. (2019). Blockchain for digital government. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Retrieved from EU Science Hub: https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/publication/eur-scientific-and-technical-research-reports/blockchain-digital-government

European Parliament. (2016). EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): Regulation (EU) 2016/679. Retrieved from Eur-Lex: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj

Facebook. (2019). The Libra Association. Retrieved from Libra: https://libra.org/en-US/association-council-principles/#libra_association_council

Ferreira, D., Li, J., & Nikolowa, R. (2019, March 25). Corporate Capture of Blockchain Governance. European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI) - Finance Working Paper No. 593/2019. Retrieved from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3320437

Hayek, F. A. (1990). Denationalisation of money: The argument refined (3rd ed.). The Institute of Economic Affairs. Retrieved from Ludwig von Mises Institute: https://mises.org/library/denationalisation-money-argument-refined

Johnson, D. (2019, September 18). Blockchain-Based Voting in the US and EU Constitutional Orders: A Digital Technology to Secure Democratic Values? European Journal of Risk Regulation, 10(2), 330–358. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2019.40

Meyer, D. (2018, July 03). Blockchain Voting Notches Another Success—This Time in Switzerland. Retrieved from Fortune: https://fortune.com/2018/07/03/blockchain-voting-trial-zug/

Nakamoto, S. (2008, October 31). Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system. Retrieved from Nakamoto Institute: https://nakamotoinstitute.org/bitcoin/

Nasdaq. (2017, January 23). Is Blockchain the Answer to E-voting? Nasdaq Believes So. Retrieved from Nasdaq: https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/blockchain-answer-e-voting-nasdaq-believes-so-2017-01-23

Nasdaq. (2018, November 13). Thailand Uses Blockchain-Supported Electronic Voting System in Primaries. Retrieved from Nasdaq: https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/thailand-uses-blockchain-supported-electronic-voting-system-primaries-2018-11-13

OECD. (2018, August 27). State-Owned Enterprises and Corruption: What Are the Risks and What Can Be Done? Retrieved from OECD: https://www.oecd.org/corporate/SOEs-and-corruption-what-are-the-risks-and-what-can-be-done-highlights.pdf

Redoano, M., & Scharf, K. A. (2004, March). The political economy of policy centralization: direct versus representative democracy. Journal of Public Economics, 88(3-4), 799-817. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0047272703000173

Rhodes, R. A. (2007, April 17). Understanding Governance: Ten Years On. Organization Studies, pp. 1-22. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233870082_Understanding_Governance_Policy_Networks_Governance_Reflexivity_and_Accountability